Every year, millions of people end up in the hospital not because their illness got worse, but because the medicine meant to help them caused harm. These are called adverse drug reactions-unexpected, dangerous side effects that can range from a nasty rash to life-threatening organ damage. For many, it’s not bad luck. It’s their genes.

Why Your Genes Matter When You Take Medicine

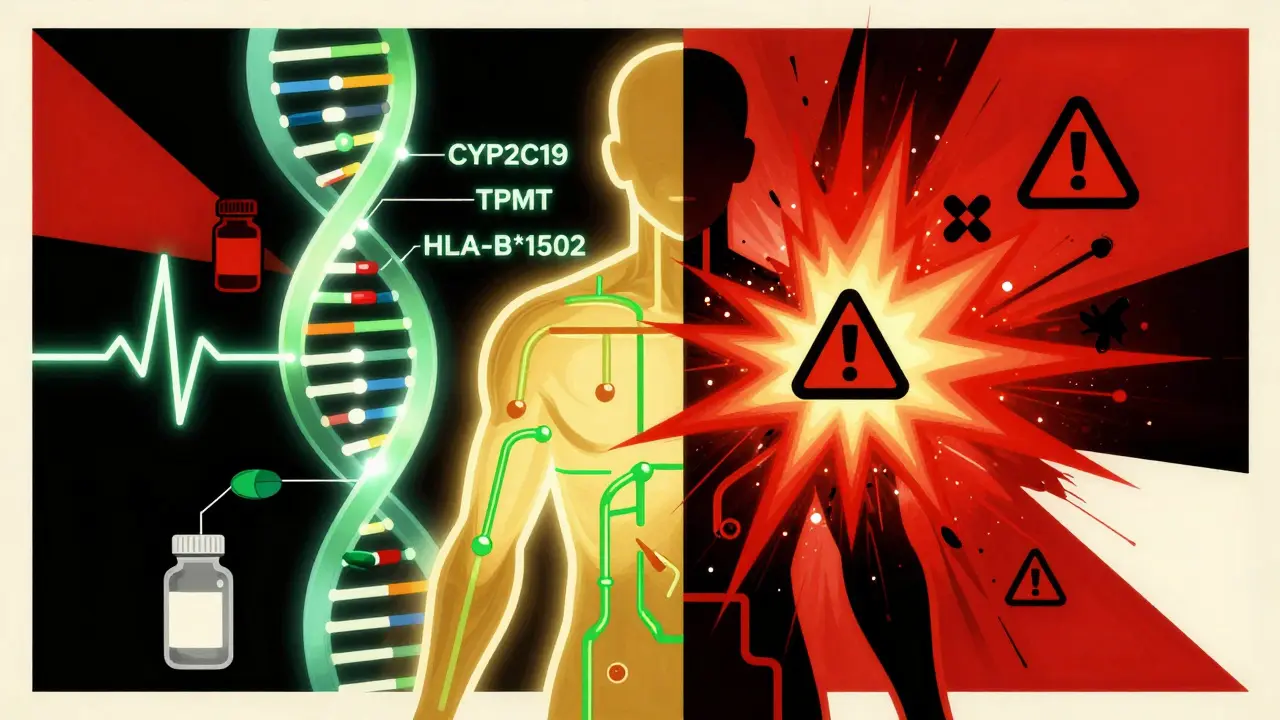

Not everyone reacts to drugs the same way. Two people taking the same pill, at the same dose, can have completely different outcomes. One feels better. The other ends up in the ER. The difference? How their body processes the drug-and that’s written in their DNA. Pharmacogenetic testing looks at specific genes that control how your body breaks down medications. Some people have versions of these genes that make them ultra-fast metabolizers, meaning drugs get cleared too quickly and don’t work. Others are slow metabolizers, so drugs build up to toxic levels. It’s not about being allergic. It’s about biology. Take carbamazepine, a common seizure and nerve pain medication. In people of Asian descent with the HLA-B*1502 gene variant, this drug can trigger Stevens-Johnson syndrome-a terrifying skin reaction that kills 1 in 5 people who get it. But if you test for that gene before prescribing the drug? You can prevent it in 95% of cases. That’s not a guess. That’s proven science.The Study That Changed Everything

In 2023, the PREPARE study, involving nearly 7,000 patients across seven European countries, gave us the clearest evidence yet. Researchers gave patients a genetic test before prescribing any medication. The test looked at 12 key genes-CYP2C19, CYP2D6, TPMT, SLCO1B1, and others-that affect how over 100 common drugs are handled by the body. The result? A 30% drop in serious adverse drug reactions. That’s not a small number. It means for every 10 people who would have had a bad reaction, three didn’t. And the test didn’t just catch one or two high-risk cases. Ninety-three percent of patients had at least one genetic variant that could change how they respond to a drug. This wasn’t rare. It was the norm. The study didn’t just prove it works-it proved it works in real hospitals, with real doctors, using real electronic health records. The results were fed directly into the system. If a doctor tried to prescribe a drug that clashed with a patient’s genes, the computer popped up a warning. No one missed it.What Genes Are Tested, and What Drugs Do They Affect?

You don’t need to test every gene in your body. Just the ones that matter for common medications. Here’s what’s typically checked:- CYP2C19: Affects clopidogrel (Plavix), used after heart attacks. If you’re a slow metabolizer, the drug won’t work-and you’re at higher risk of another heart attack.

- TPMT: Critical for azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine, used in autoimmune diseases and cancer. Without testing, up to 1 in 3 patients can develop deadly bone marrow suppression.

- SLCO1B1: Determines how your body handles statins like simvastatin. A certain variant increases muscle damage risk by 4x.

- DPYD: Used before giving fluorouracil (a chemo drug). People with this variant can die from toxicity if dosed normally.

- HLA-B*1502: As mentioned, prevents deadly skin reactions to carbamazepine and phenytoin.

How It Works in Practice

Getting tested isn’t complicated. A simple cheek swab or blood draw is all it takes. Results come back in 24 to 72 hours. In hospitals that have integrated this into their systems, the report shows up right in the doctor’s electronic chart. The system doesn’t just say, “You have a variant.” It tells the doctor what to do: “Avoid this drug. Use an alternative. Lower the dose.” The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) has published clear guidelines for over 30 gene-drug pairs. These aren’t opinions. They’re evidence-based rules, updated every quarter. At the University of Florida, since they started preemptive testing in 2012, emergency visits due to drug reactions dropped by 75%. The initial cost? $1.2 million. The payback? Less than two years-from avoided hospital stays, fewer lab tests, and less time lost to side effects.Why Isn’t Everyone Doing This Yet?

If it’s this effective, why aren’t all doctors ordering these tests? One reason: cost. A full panel runs $200 to $500. That’s not cheap. But consider this: a single hospitalization for a bad drug reaction can cost $20,000 to $50,000. The NHS in the UK estimates that adverse drug reactions cause 7% of all hospital admissions-costing half a billion pounds a year. Testing saves money. Another problem: doctors don’t feel trained. Only 37% of physicians feel confident interpreting these results. Many don’t know what “intermediate metabolizer” means, or how to adjust a dose. That’s why training matters. Hospitals that succeed invest in education-4 to 8 hours of CME-certified training for staff. There’s also a gap in data. Most genetic studies were done in people of European descent. That means for African, Indigenous, or Asian populations, we still don’t know all the variants that matter. But new research is fixing that. The NIH is now adding over 100 new gene-drug links from underrepresented groups. That’s progress.What About Privacy and Ethics?

Some people worry: “If my genes show I react badly to a drug, could my insurance use that against me?” In the U.S., GINA-the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act-makes it illegal for health insurers and employers to use genetic data to deny coverage or employment. That protection is strong. But it doesn’t cover life insurance or long-term care. That’s a gray area. Still, most patients are on board. Eighty-five percent say they’d take the test if their doctor recommended it. Only a third have privacy concerns-and many of those would feel better knowing their data is stored securely and only used for treatment decisions.

What’s Next?

The future isn’t just single-gene tests. Researchers are starting to combine multiple genetic signals into polygenic risk scores-looking at dozens of small variations at once to predict how you’ll respond to a drug. Early results show these can improve accuracy by 40% to 60%. Costs are falling too. Pilot projects are testing point-of-care devices that could bring the price of a full panel down to $50 by 2026. Imagine getting your results before you leave the clinic. And adoption is growing. By 2026, 87% of major U.S. medical centers plan to offer preemptive pharmacogenetic testing. In Europe, the EU is investing €150 million to roll it out nationally.Who Should Get Tested?

You don’t need to wait for a bad reaction to act. The best time to test is before you start any new medication-especially if you’re:- Taking multiple drugs (polypharmacy)

- On antidepressants, blood thinners, or pain meds

- Have had a bad reaction to a drug before

- Are of Asian, African, or Indigenous descent (where certain variants are more common)

- Have a family history of unexpected drug side effects

Bottom Line: It’s Not Science Fiction

Pharmacogenetic testing isn’t a future promise. It’s here. It works. And it’s saving lives right now. The data is solid. The guidelines are clear. The cost is justified. The only thing holding it back is awareness-and a little bit of inertia. If you’re a patient, ask your doctor: “Could my genes affect how I respond to this medicine?” If you’re a provider, start small. Test for CYP2C19 before prescribing clopidogrel. Test for TPMT before azathioprine. Build from there. Adverse drug reactions aren’t inevitable. They’re preventable. And your genes hold the key.Is pharmacogenetic testing covered by insurance?

In the U.S., Medicare and some private insurers cover pharmacogenetic testing for specific high-risk drug-gene pairs, like CYP2C19 before clopidogrel or TPMT before thiopurines. Coverage for broader panels varies by plan. Always check with your insurer before testing. In Europe, national health systems are increasingly covering preemptive testing following the PREPARE study results.

How long does it take to get results?

Most clinical labs deliver results within 24 to 72 hours. Some hospital systems with in-house testing can return results in under 24 hours. Point-of-care devices currently in development aim to cut this to under an hour by 2026.

Can I get tested without a doctor’s order?

Direct-to-consumer tests like 23andMe offer limited pharmacogenetic data, but they’re not clinically validated for medication decisions. For reliable, actionable results, you need a test ordered by a healthcare provider and interpreted through clinical guidelines like CPIC. Consumer tests lack the depth and context needed for safe prescribing.

Does pharmacogenetic testing replace therapeutic drug monitoring?

No-it complements it. Therapeutic drug monitoring measures drug levels in your blood after you’ve taken the medicine. Pharmacogenetic testing tells you how your body will process the drug before you even take it. One is reactive; the other is proactive. Used together, they give the best safety profile.

Are there risks to getting tested?

The physical risk is minimal-a cheek swab or blood draw. The main risks are psychological (worrying about results) or privacy-related. But under U.S. law (GINA), health insurers and employers cannot use genetic data to deny coverage or employment. Results are protected under HIPAA like any other medical record.

What if I already had a bad reaction to a drug?

You still benefit from testing. Knowing your genetic profile helps avoid repeating the same mistake. It also helps your doctor choose safer alternatives for future prescriptions. Reactive testing after an event is less effective than preemptive testing-but it’s still better than nothing.

Will my test results be shared with other doctors?

Yes, if you’re in a system with integrated electronic health records, your results can be accessed by any provider treating you-unless you opt out. That’s a major advantage: your pharmacogenetic profile becomes part of your lifelong medical record, helping every doctor who treats you in the future.

How often do I need to be tested?

Once. Your genes don’t change. A single test can guide your medication choices for life. Some labs offer lifetime storage of your results, so you never need to retake the test unless a new gene-drug pair becomes clinically relevant.