HPV is not just a common sexually transmitted infection-it’s the leading cause of cervical cancer and several other cancers in both men and women. Yet most people don’t know how easily it can be prevented. The good news? We have powerful tools: vaccines that stop infection before it starts, screening tests that catch abnormal cells years before they turn cancerous, and clear guidelines that make prevention simple-if you know what to do.

What Is HPV, and Why Should You Care?

Human papillomavirus (HPV) isn’t one virus. It’s a family of over 200 related viruses. About 40 of them affect the genital area. Most are harmless and clear on their own within a year or two. But 14 types are considered high-risk because they can stick around and cause cell changes that lead to cancer.

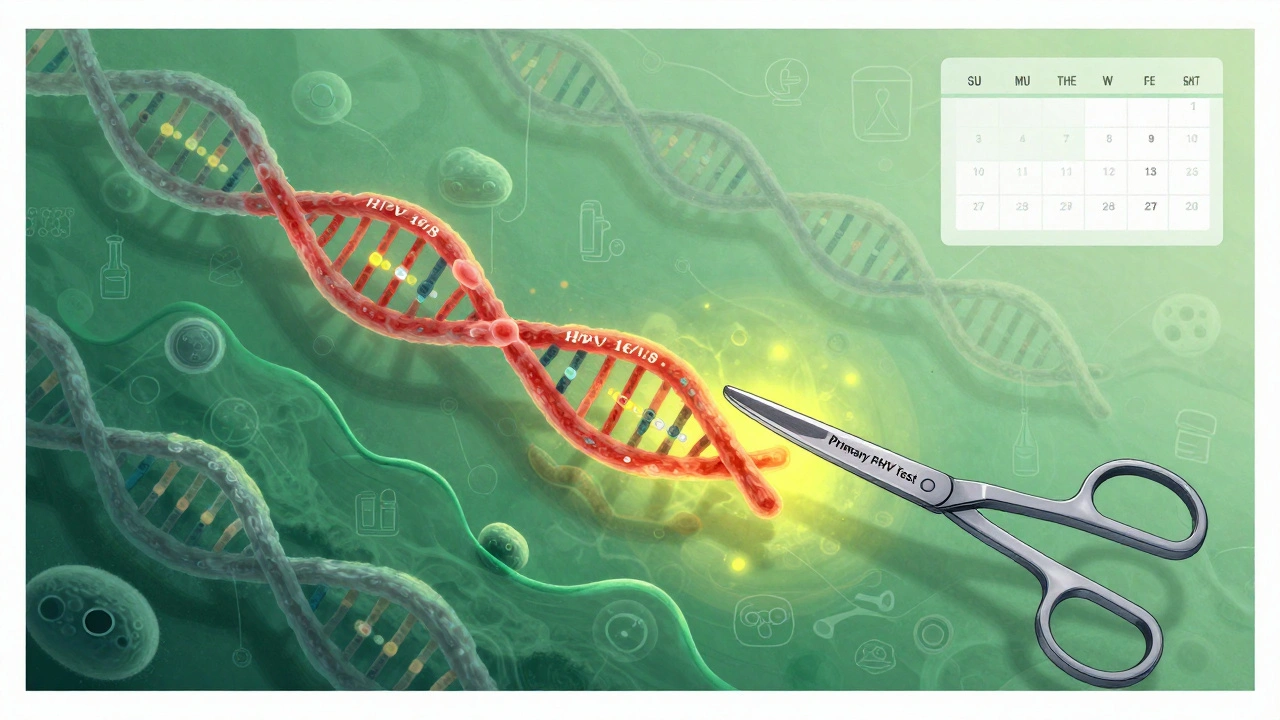

HPV 16 and HPV 18 are the worst offenders. Together, they cause about 70% of all cervical cancers. They’re also linked to cancers of the vulva, vagina, penis, anus, and throat. The scary part? You can have HPV for years without symptoms. No itching, no discharge, no pain. That’s why screening and vaccination aren’t optional-they’re lifesavers.

How the HPV Vaccine Stops Cancer Before It Starts

The HPV vaccine isn’t just a shot-it’s a cancer prevention tool. The current vaccine, Gardasil 9, protects against nine types of HPV, including the two most dangerous ones (16 and 18) and five others that cause most remaining cases.

It works best when given before any sexual contact. That’s why the CDC recommends vaccination for all kids at age 11 or 12. But it’s not too late for older teens and young adults. The vaccine is approved for people up to age 45. Even if you’ve had HPV before, the vaccine can still protect you against other strains you haven’t encountered.

Studies show the vaccine reduces precancerous cervical lesions by over 90% in vaccinated groups. In countries with high vaccination rates-like Australia and Sweden-cervical cancer rates in young women have dropped by more than 80% since the vaccine was introduced. The science is clear: if you’re eligible, get the vaccine.

Screening Has Changed-Here’s What You Need to Know Now

For decades, the Pap test was the gold standard. It looked at cervical cells under a microscope to spot abnormalities. But it missed a lot. Now, screening has shifted to detecting the virus itself, not just its damage.

Primary HPV testing is now the preferred method for people aged 25 to 65, according to the American Cancer Society and other major groups. This test checks for DNA or RNA from high-risk HPV types (14 total), not just 16 and 18. Two FDA-approved tests are widely used: the cobas HPV Test and the Aptima HPV Assay.

Why is this better? HPV testing finds more precancers early. A 2018 JAMA study showed it’s 94.6% sensitive for detecting serious cell changes, compared to just 55.4% for Pap tests alone. That means fewer cancers slip through the cracks.

How Often Should You Get Screened?

Screening intervals have gotten longer because the tests are more reliable. Here’s what the current guidelines say:

- Ages 21-24: No HPV testing. Pap test every 3 years if needed.

- Ages 25-65: Primary HPV test every 5 years (preferred option).

- Ages 30-65: You can also choose Pap test every 3 years, or both tests together (cotesting) every 5 years.

Even if you’ve been vaccinated, you still need screening. The vaccine doesn’t protect against all cancer-causing HPV types, and it doesn’t clear existing infections. Screening is for everyone-vaccinated or not.

What Happens If Your HPV Test Is Positive?

A positive HPV test doesn’t mean you have cancer. It just means the virus is present. Most infections go away on their own. But if you test positive, the next steps depend on your age and the type of HPV.

If you’re 25 or older and test positive for HPV 16 or 18, you’ll usually get a colposcopy-a quick exam where a doctor looks at your cervix with a magnifying tool. If you test positive for other high-risk types but not 16 or 18, you’ll often get a Pap test as a follow-up. If both are abnormal, you’ll likely need a colposcopy.

Many people panic when they get a positive result. But the system is designed to catch problems early. Less than 1% of women with a positive HPV test will develop cancer within 5 years. That’s why the 5-year screening interval is safe-it gives your body time to clear the virus before intervention is needed.

Self-Collection Is Changing the Game

One of the biggest barriers to screening? Discomfort, fear, or lack of access. Many women skip Pap tests because they’re embarrassed, busy, or live far from clinics.

Now, self-collected HPV tests are approved and recommended. You can swab your own vagina at home, mail in the sample, and get results just like a clinic visit. A 2024 Kaiser Permanente study found self-collected tests are 84.4% as sensitive as clinician-collected ones-with 90.7% specificity. That’s nearly as accurate.

Real-world data from Australia and the Netherlands show self-collection increases screening rates by 30-40% among people who hadn’t been screened in years. The USPSTF now lists self-collection as a valid option. This isn’t the future-it’s happening now.

Why Disparities Still Exist-and What’s Being Done

Despite all the progress, cervical cancer isn’t equal. Black women in the U.S. are 70% more likely to die from it than White women. In low-income countries, only 19% of women have ever been screened. In the U.S., 30% of cervical cancers occur in women who’ve never had a Pap test.

These gaps exist because of systemic barriers: lack of insurance, transportation, cultural stigma, language barriers, and under-resourced clinics. The WHO’s 90-70-90 goal by 2030 aims to fix this: 90% of girls vaccinated by 15, 70% of women screened by 35 and 45, and 90% of abnormal cases treated.

Here in the U.S., community health centers and mobile clinics are starting to offer self-collection kits in pharmacies, libraries, and schools. Some states now cover self-collection under Medicaid. These efforts are saving lives.

What’s Next for HPV Prevention?

The next wave of innovation is already here. AI is being used to analyze Pap smears faster and more accurately. Paige.AI received FDA approval in January 2023 for its AI system that helps pathologists spot precancerous cells.

Research also suggests that after two or three negative HPV tests, screening every 6 years may be safe. Studies from Wayne State University show the risk of cervical cancer drops to less than 2.5 per 1,000 after two negative HPV tests-lower than the risk after a single negative Pap test.

By 2025, primary HPV testing will likely be the standard in most U.S. clinics. The goal isn’t just to reduce cancer-it’s to eliminate it as a public health threat. The WHO estimates that with full implementation of vaccination, screening, and treatment, we could prevent 62 to 77 million cervical cancer cases over the next century.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re under 26: Get the HPV vaccine if you haven’t already. It’s covered by most insurance, including Medicaid and the Vaccines for Children program.

If you’re 25-65: Ask your provider for a primary HPV test every 5 years. If you’ve been getting Pap tests, ask if you can switch. If you’ve avoided screening because of discomfort, ask about self-collection kits.

If you’re over 65: You may not need screening anymore-if you’ve had regular tests and no history of abnormalities. But talk to your doctor. Some people need continued screening based on past results.

HPV doesn’t care if you’re rich or poor, vaccinated or not. But your choices do matter. Getting vaccinated and screened isn’t just about protecting yourself. It’s about protecting the people around you-and breaking the cycle of preventable cancer.