Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, affecting up to 90% of people with an overactive thyroid in countries with enough iodine in their diet. It’s not just a thyroid problem-it’s an autoimmune disorder where your body’s own immune system attacks your thyroid gland, forcing it to pump out too much hormone. This leads to a cascade of symptoms that can feel overwhelming: racing heart, weight loss despite eating more, shaking hands, trouble sleeping, and even bulging eyes. If you’ve been told you have Graves’ disease, you’re not alone. About 1 in 50 women and 1 in 200 men will develop it in their lifetime, with most cases showing up between ages 30 and 50.

How Graves’ Disease Actually Works

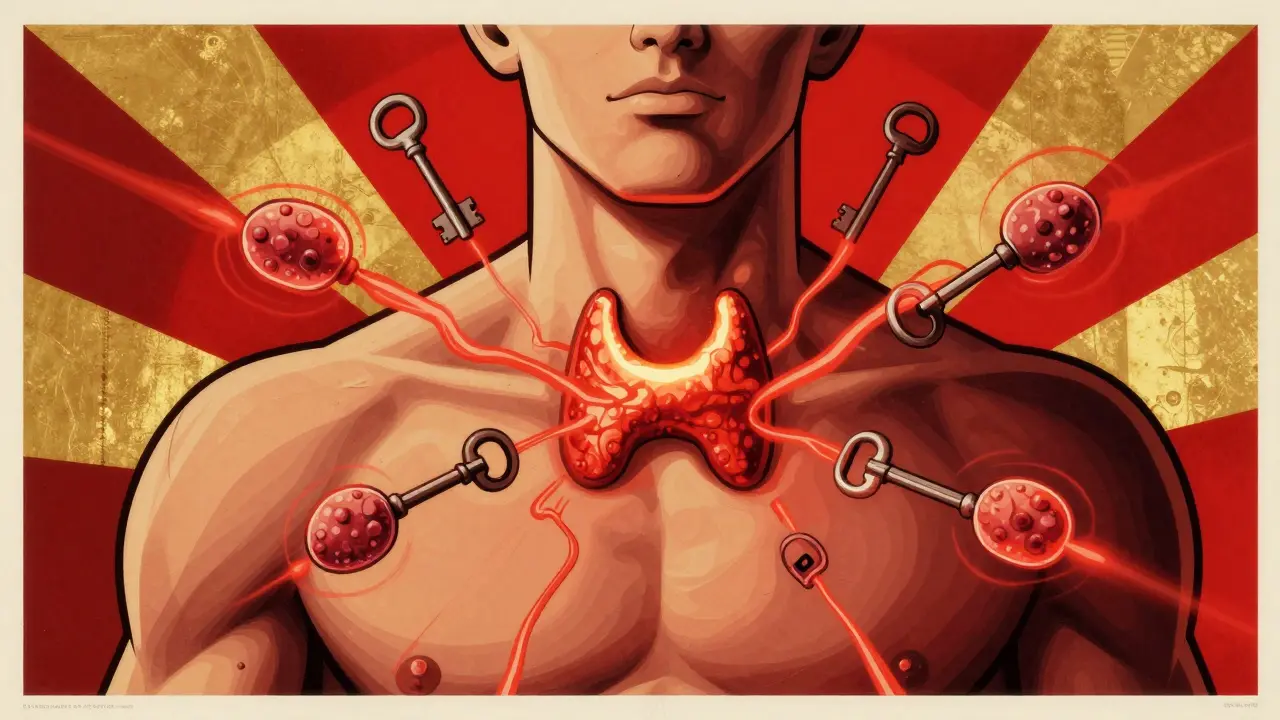

Normally, your thyroid works like a thermostat. Your brain sends a signal (TSH) to tell it how much hormone to make. In Graves’ disease, that system breaks down. Instead of TSH, your immune system creates abnormal antibodies called thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI). These antibodies latch onto the same receptors on your thyroid that TSH normally binds to-but they don’t turn off. They keep the thyroid in overdrive, producing too much T3 and T4.

This isn’t random. Genetics play a big role. If someone in your family has Hashimoto’s, type 1 diabetes, or rheumatoid arthritis, your risk goes up. Women are 7 to 8 times more likely to get it than men. Smoking doesn’t just hurt your lungs-it triples your chance of developing the eye complications tied to Graves’ disease. And if you’ve recently had a baby, your risk spikes for a year or two after delivery.

What Symptoms to Watch For

The symptoms of Graves’ disease vary by age and how long it’s been going on. Younger people often feel like they’re wired: anxious, jittery, unable to sit still, losing weight even when eating more, sweating through clothes in cool rooms, and having heart palpitations that feel like your chest is rattling. You might notice your hands trembling when you hold a cup, or your muscles feel weak climbing stairs.

Older adults don’t always show the classic signs. Instead, they might feel unusually tired, have chest pain, forget things more often, or develop an irregular heartbeat that feels like fluttering. Sometimes, the only clue is a new diagnosis of atrial fibrillation.

One-third of people with Graves’ disease develop eye problems-called Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Your eyes may bulge forward, feel dry or gritty, water excessively, or double when you look side to side. In rare but serious cases, vision can be threatened. Less common is pretibial myxedema: thick, red, lumpy skin on the shins. It’s rare, affecting only 1-4% of patients, but it’s a clear sign the immune system is attacking more than just the thyroid.

How Doctors Diagnose It

Diagnosis starts with a blood test. The first clue is a very low TSH level-often below 0.4 mIU/L. At the same time, free T4 and T3 levels are high. That combination is a red flag for hyperthyroidism. But to confirm it’s Graves’ disease, doctors test for specific antibodies: TSI and TRAb. These are found in 85-95% of people with Graves’, and a positive result means you don’t need more tests.

If antibody tests aren’t available, a radioactive iodine uptake scan can help. In Graves’ disease, the thyroid soaks up way more iodine than normal-usually over 40% in 24 hours. That’s different from other causes of hyperthyroidism, like a toxic nodule, which shows up as a hot spot on the scan.

Ultrasound is also becoming more common. It can show increased blood flow in the thyroid, which looks like a “thyroid storm” of vessels. This method is useful when you can’t have radioactive tests-like during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Three Main Treatment Paths

There are three approved treatments for Graves’ disease. None is perfect. Each has trade-offs, and the best choice depends on your age, symptoms, whether you have eye disease, and what you’re comfortable with long-term.

1. Antithyroid Medications

Methimazole is the first choice for most adults. It blocks the thyroid from making too much hormone. You start with a higher dose-usually 10 to 40 mg a day-and then reduce it once your levels stabilize. Propylthiouracil is used less often because it carries a higher risk of liver damage. It’s mainly used in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Most people take these pills for 12 to 18 months. About 30-50% go into remission after that. Your chances are better if your thyroid is only slightly enlarged, your antibody levels drop to zero by the end of treatment, and you don’t smoke. But if you miss doses, your risk of relapse jumps by 40-50%.

Side effects are rare but serious. Agranulocytosis-a sudden drop in white blood cells-can happen in 1 out of every 500 people. If you get a fever over 100.4°F with a sore throat, stop the medicine and get blood work right away. Liver problems are also possible, so your doctor will check your liver enzymes every few months.

2. Radioactive Iodine (I-131)

This is the most common treatment in the U.S. You swallow a capsule or liquid containing a small amount of radioactive iodine. Your thyroid absorbs it like regular iodine, and the radiation slowly destroys the overactive cells. Within 6 to 12 months, most people become hypothyroid-meaning their thyroid stops working entirely.

The big advantage? It’s a one-time treatment. No more daily pills. The downside? You’ll need to take levothyroxine for the rest of your life. Dosing starts at about 1.6 mcg per kg of body weight. You’ll need blood tests at 4 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after treatment to adjust the dose.

Radioactive iodine can make eye disease worse, especially in smokers. That’s why doctors often delay it or give steroids first if you have moderate-to-severe eye symptoms. It’s also not used during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

3. Thyroid Surgery (Thyroidectomy)

Surgery removes the entire thyroid. It’s usually reserved for people with very large goiters that press on the windpipe or esophagus, those who can’t take medications or radioactive iodine, or those who want a fast, permanent solution.

Success rates are over 95%. But it’s not risk-free. There’s a 1-2% chance of damaging the parathyroid glands, which control calcium levels. A 0.5-1% risk of injuring the nerve that controls your voice means your voice could become hoarse. You’ll also need lifelong thyroid hormone replacement.

Recovery is usually quick. Most people go home the same day or the next day. Pain is mild, and you can return to normal activities in about a week.

Treating Graves’ Eye Disease

Eye symptoms can be the most distressing part of Graves’ disease. Mild cases often improve with simple steps: quit smoking, use artificial tears, sleep with your head elevated, and wear sunglasses. Selenium supplements (100 mcg twice a day for 6 months) can reduce swelling and discomfort in mild cases, according to guidelines from the American Thyroid Association.

For moderate-to-severe eye disease, intravenous steroids are the standard. You get 500 mg of methylprednisolone once a week for 6 weeks, then 250 mg weekly for another 6 weeks. About 60-70% of people see real improvement in swelling and vision.

A newer drug called teprotumumab is changing the game. It targets the insulin-like growth factor receptor, which plays a key role in eye inflammation. In clinical trials, 75-80% of patients saw a big drop in eye bulging, and nearly 70% had significant improvement compared to just 20% on placebo. It’s not yet widely available, but it’s becoming an option for those who don’t respond to steroids.

If eye pressure threatens your vision, orbital decompression surgery may be needed. This removes bone from around the eye socket to give the swollen tissue more room. It’s usually done after inflammation is under control.

What Life Looks Like After Treatment

Many people feel better within weeks of starting treatment. Heart palpitations fade. Energy returns. Sleep improves. But recovery isn’t always linear. Some people cycle through periods of feeling great and then crashing-especially if their medication dose isn’t quite right.

After radioactive iodine or surgery, you’ll need to take thyroid hormone pills every day. Missing even one dose can make you feel sluggish or depressed. Regular blood tests every 6-12 months are non-negotiable.

One of the biggest regrets patients report is not being fully warned about lifelong hormone replacement after radioactive iodine. Many assumed it was a “cure,” not a switch from one problem to another.

Smoking cessation is the single most powerful thing you can do to protect your eyes and reduce relapse risk. Studies show smokers are 7-8 times more likely to develop severe eye disease than non-smokers.

What’s Next in Research

Scientists are exploring new treatments. One promising area is B-cell depletion therapy using drugs like rituximab, which targets the immune cells making the harmful antibodies. Early trials show a 60% response rate in eye disease. Genetic studies have identified over a dozen genes linked to Graves’ disease, including HLA-DQA1 and CTLA4. This could lead to personalized treatments based on your genetic profile.

For now, the goal is simple: control the hormone levels, protect your eyes, and give you your life back. With the right treatment, most people with Graves’ disease live full, healthy lives.